The first Native American pro baseball player was Louis Sockalexis. He was nicknamed “Chief,” the first of a long line of “Chiefs” in Major League ball. It’s interesting that Indians were allowed to be pro ball players while African Americans were banned. In fact more than one black player tried to plead the case that they were Indian, not African, always to no avail. A full blooded Penobscot Indian, Sockalexis played for the Cleveland American League baseball club in the late 19th century. While “Chief Meyers” and “Chief Bender” later became bonafide stars, Sockalexis’ career was short. He succumbed to alcoholism and other ailments and was out of baseball after three short seasons. But for a short time he was beloved in Cleveland and made such an impression on the fan base that two years after his death in 1915, the Cleveland franchise was re-named, in a popular vote, the Indians, after him. So his legacy lived on in name and, unfortunately, in the racist logo the Indians used, unbelievably, until just this year.

The first Native American pro baseball player was Louis Sockalexis. He was nicknamed “Chief,” the first of a long line of “Chiefs” in Major League ball. It’s interesting that Indians were allowed to be pro ball players while African Americans were banned. In fact more than one black player tried to plead the case that they were Indian, not African, always to no avail. A full blooded Penobscot Indian, Sockalexis played for the Cleveland American League baseball club in the late 19th century. While “Chief Meyers” and “Chief Bender” later became bonafide stars, Sockalexis’ career was short. He succumbed to alcoholism and other ailments and was out of baseball after three short seasons. But for a short time he was beloved in Cleveland and made such an impression on the fan base that two years after his death in 1915, the Cleveland franchise was re-named, in a popular vote, the Indians, after him. So his legacy lived on in name and, unfortunately, in the racist logo the Indians used, unbelievably, until just this year.

Sockalexis had to patrol one of the oddest outfields in baseball. As was often the case with ballparks of the era, the field dimensions of League Park were heavily influenced by the idiosyncrasies of the property it was built on. A saloon owner and several home owners refused to sell resulting in the right field foul pole being a mere 280 ft from home plate, the left field pole a hefty 375 ft. away and center field a whopping 460ft. The Cleveland ball club, then called the Spiders, moved into League Park in 1891 and ten years later, two years after Sockalexis’ departure, and 4 years before his death, they were made a charter member of the newly formed 8 team American League. League Park remained the home of the Indians for 37 seasons. With a capacity of only 28,000 it was bound to be replaced as baseball’s popularity continued to rise, even during the depression. But who would have thought the change would be so extreme.

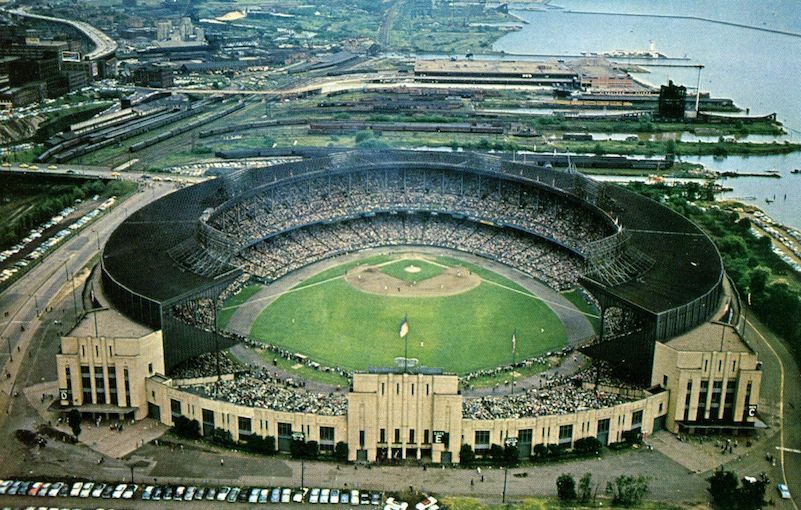

In an attempt to attract the Olympics, the city of Cleveland began construction of a huge stadium on the shores of Lake Erie in 1930. While the Olympic effort failed, Los Angeles was the winner, the immense, symmetrical stadium had the largest capacity in all baseball. On July 31, 1932 the inaugural game hosted the largest crowd ever to see a Major League ballgame. 76,979 fans showed up to see Lefty Grove of the Philadelphia A’s beat Indian, Mel Harder, 1-0, this in the middle of the depression. At first, Municipal Stadium was a great success. The team was stacked and Clevelanders flocked to see their Indians. A league attendance record of 2,607,627 was set in 1949. Riding the mighty arm of Bob Feller, the Indians won the World Series in 1954, the one and only championship of the franchise to this day. Ultimately, however, its vastness and location became an albatross around its neck. Attendance dipped as the team languished and the cold winds continued to blow across the lake into the north facing stands. Municipal Stadium had not been designed for baseball in the first place and came to be famously dubbed, “The Mistake By the Lake.”

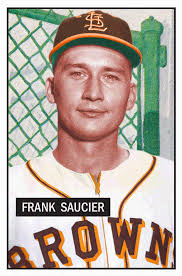

On a personal note, Municipal Stadium was the site of my Dad’s college roommate’s only hit in his very brief, but strangely notable, major league career. In 1951, playing for the St Louis Browns, Frank Saucier hit a double off the distant center field wall (470 ft). He was a great player in the minors who in 1949 batted .446 for Wichita Falls in the Texas League, the highest average in all organized professional baseball, and in 1950 was named the Sporting News Minor League Player of the Year. 91 and living in Amarillo, he remembers that hit 69 years later. “It was off of Mike Garcia, a pretty fair pitcher” he told me not long ago. He was also involved in one of baseball’s all time oddest moments. Just a year later, playing hurt, he was about to bat when he was called back to the dugout. A little man, all of 3’ 4”, walked past him, showed a signed contract to the umpires, crouched even lower, and pinch hit for Frank. The Brown’s owner, Bill Veeck, had signed a midget as a publicity stunt and yes, it was Frank Saucier he pinch hit for. Once word got out Eddie Gaedel was banned and Veeck fined, but not before Gaedel officially walked. You can look it up.

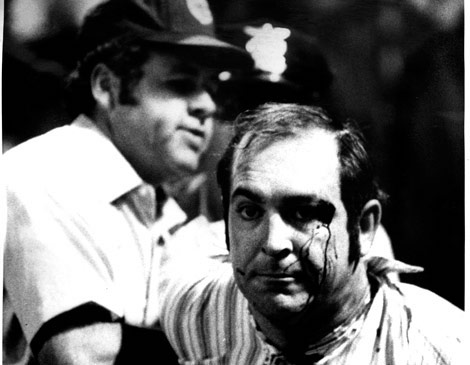

Some 23 years later Bill Veeck was still up to his tricks, this time with much worse consequences. In 1974 Bill was owner of the Indians and in a desperate way financially. How else to explain “10 Cent Beer Night”. Veeck (as in Wreck) unfortunately forgot, one presumes, that “Bat Night” had occurred a few nights previously. Well, some of those bats were still around and by the ninth inning things got out of control. Even though the Indians were staging a ninth inning comeback with two men on base and the score tied, drunken bat wielding fans stormed the field and security was unable to shepherd them back into the stands. There was blood, and the game the game was ultimately forfeited to the Texas Rangers.

Some 23 years later Bill Veeck was still up to his tricks, this time with much worse consequences. In 1974 Bill was owner of the Indians and in a desperate way financially. How else to explain “10 Cent Beer Night”. Veeck (as in Wreck) unfortunately forgot, one presumes, that “Bat Night” had occurred a few nights previously. Well, some of those bats were still around and by the ninth inning things got out of control. Even though the Indians were staging a ninth inning comeback with two men on base and the score tied, drunken bat wielding fans stormed the field and security was unable to shepherd them back into the stands. There was blood, and the game the game was ultimately forfeited to the Texas Rangers.

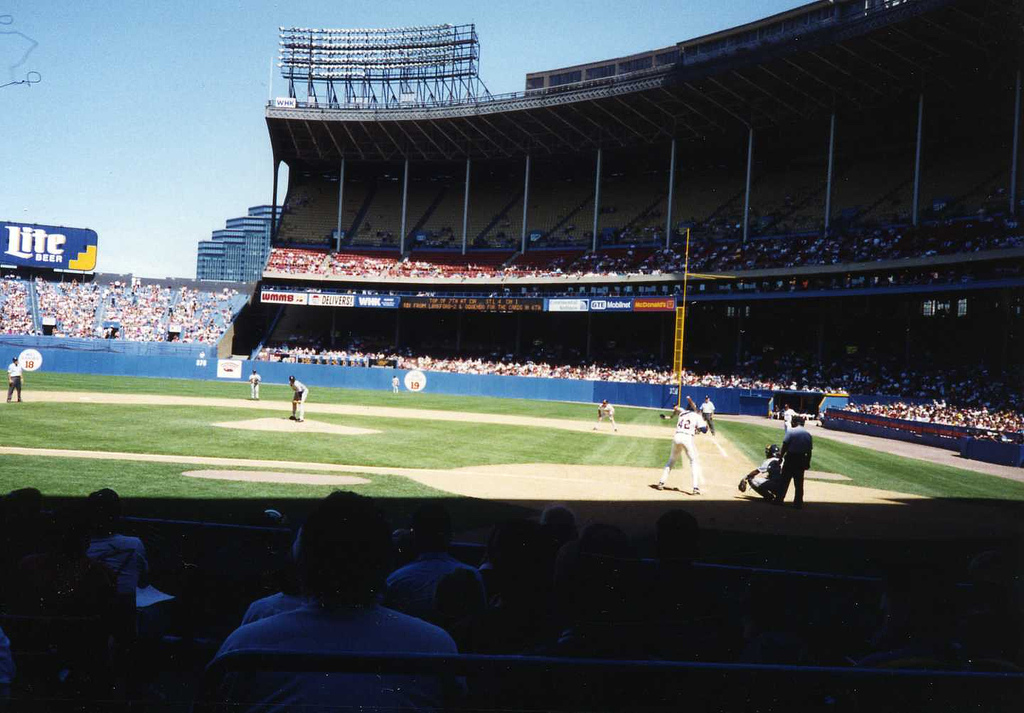

During its last season in 1993, my friend Alec Marsh and I made a pilgrimage to Municipal Stadium and watched three games. It was a simply glorious weekend. We experienced none of the cold, biting wind off the lake that Municipal Stadium was famous for. Even though the team was very good, and would shortly contend with stars Kenny Lofton, Albert Belle and Jim Thome, it still felt cavernous, with vast sections empty of fans. The view of the Lake was beautiful, but you had no sense of being in the middle of a major American city watching an up and coming team filled with potential and future hall of famers.

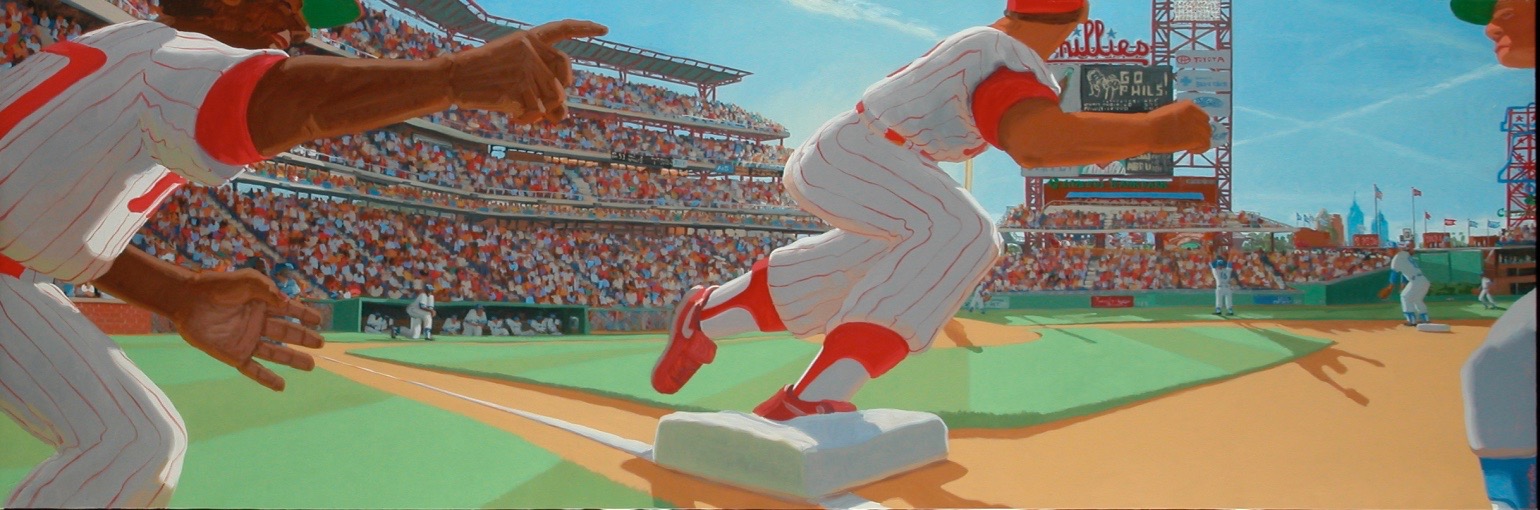

Two years later that same team hosted the World Series in a sparkling new downtown ballpark, Jacobs Field (since renamed, in the current fashion, Progressive Field). Jacobs Field was a part of the downtown revitalization of Cleveland, and the drawing power of the Indians was a great boon to the city. The Indians had five consecutive first place finishes, were in the Series again in ’95 and ’97 although, alas, they fell short both times, losing first to the Atlanta Braves and in ‘97 to the upstart Florida Marlins in agonizing fashion. On the plus side, Jacobs Field hosted an amazing 455 consecutive sell outs during these halcyon years. The excellence of the team and the magnificent HOK designed ball park made for a fun, exciting evening at the “ole’ ball yard.”

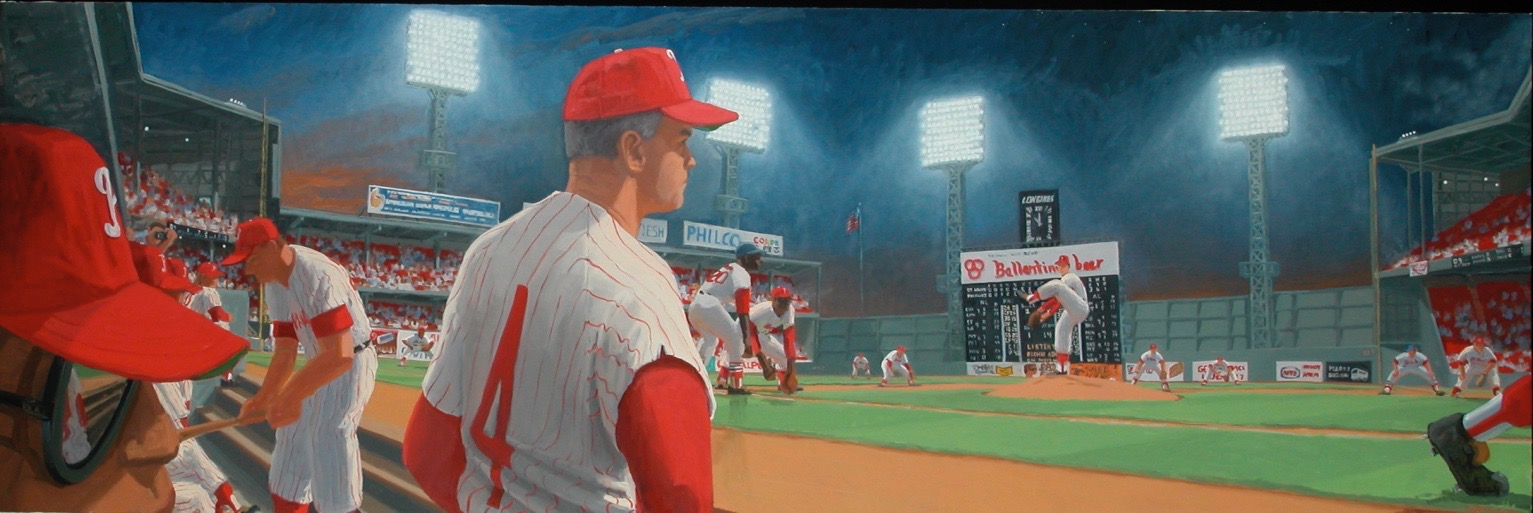

It was another gorgeous summer evening when I visited. Before the game, a rock band performed on the concourse, a nod to Cleveland’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The aroma and smoke of mid-west barbeque and sausages filled the air. The days of sellouts was long past, but it was a good crowd, partly owing to its being “Dollar Dog night” (not Beer Night, alas!), and fans streamed up the aisles with their flimsy cardboard boxes filled with hot dogs and plastic cups of beer. I hadn’t expected to see so many red “Make America Great Again” ball caps, due undoubtably to my denial of the political realities of north central Ohio. As the sun set, with Lake Erie barely visible in the distance, the shadows of the light towers crept out across the field. The beautifully mowed grass shimmered. And the cartoon image of an American Indian perched on top of the scoreboard looked down, his nose a grotesque hook, his eyes triangular like teepees, on an idyllic American scene.

“Dollar Dog Night, Progressive Field, Cleveland, Ohio”, oil on canvas, 48” x 60”, 2018

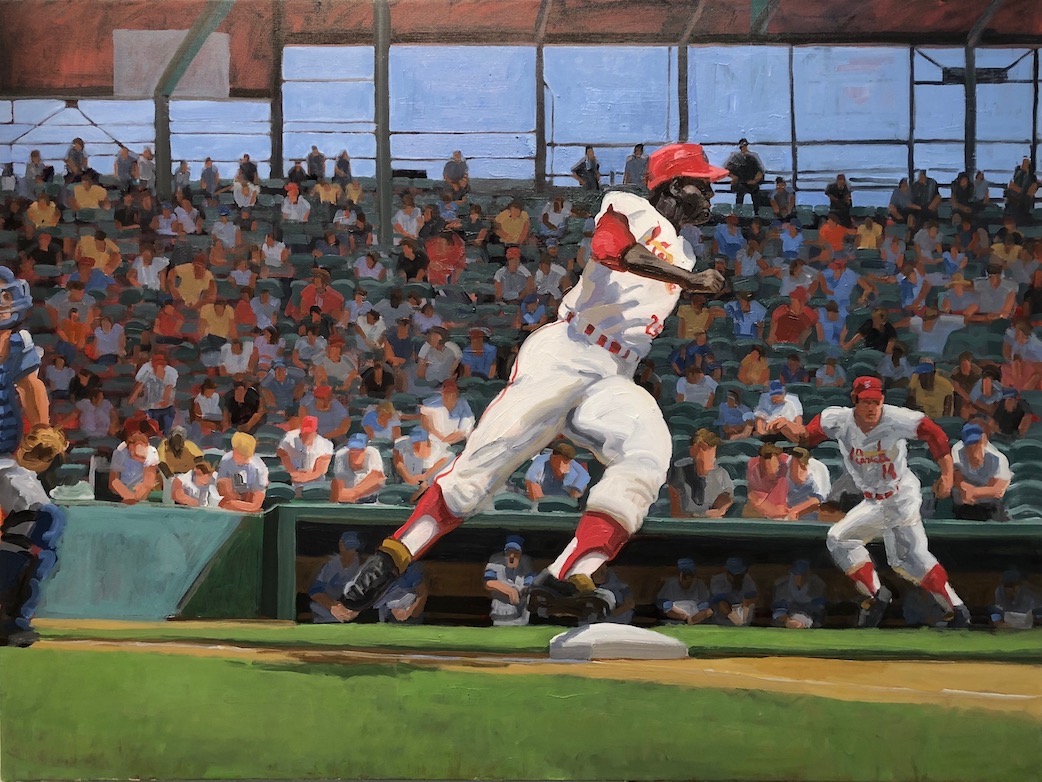

Scoreboard detail showing Louis Sockalexis as batting.